At some point in the interesting new movie Frances Ha someone declares: “Twenty-seven is old.” In his enthusiastic review film critic A.O. Scott observes: “while that may in some sense be true, it is also true that 27 is not as old as it used to be. A few short generations ago members of the American middle class could be expected to reach that age in possession of a career, a spouse and at least one child, unless they were rock stars, in which case they would be dead.”

I don’t know whether Scott was referring to his generation or his mother’s (his mother’s, since I know his mother, the amazing Joan Scott, would be mine), or further back in time. But it got me thinking. Did I consider myself old at twenty-seven?

I turned twenty-seven in 1968, when this photograph was taken. I had been back living in New York after spending a good chunk of my twenties in Paris. That’s the story of my new memoir. The haircut, which didn’t last long, was the sign of my continued fascination with Jean Seberg and the movie Breathless, the cultural artifact that presides over my memoir. My curly hair even straightened and cut to an inch of its life refused to cooperate.

I turned twenty-seven in 1968, when this photograph was taken. I had been back living in New York after spending a good chunk of my twenties in Paris. That’s the story of my new memoir. The haircut, which didn’t last long, was the sign of my continued fascination with Jean Seberg and the movie Breathless, the cultural artifact that presides over my memoir. My curly hair even straightened and cut to an inch of its life refused to cooperate.

In 1968 I had neither a career, a spouse, nor a child; I considered myself lucky to have a new cool boyfriend (who took this picture), a goddaughter―the daughter of my Paris roommate―and, not least, to be starting graduate school at Columbia.

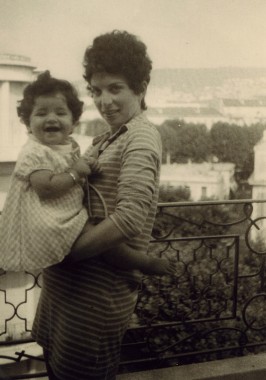

My lovely goddaughter Annabel in Nice. My hair back to normal.

My lovely goddaughter Annabel in Nice. My hair back to normal.

Above all, it was 1968, and even if I had managed to miss the student revolts both in Paris and New York, it was clear that something new was happening for young people. But I would also have to say that I did feel old, in part because I was older than my graduate school cohort; in part because I felt that I had drifted through the first half of my twenties and had little to show for it. (OK, I had survived a bad marriage, but still.) I was kind of embarrassed to be twenty-seven and still in school, still getting bailed out financially by my parents from time to time—what Scott refers to as the “quarter-life crisis.”

Despite his references to generations, Scott does not see this movie as primarily about a generation, but rather, and I agree, the story of Frances’s journey to the shot in the final scene that gives the movie its title (to explain that, the sweetest image of the film would definitely be a spoiler), and makes twenty-seven seem more exciting about what is to come than weary from the mishaps leading up to that moment.

Another reviewer calls Frances Ha “the best film that will be made about this generation,” by which he means “people in their late twenties right about now,” but I’m not at all sure that this is a generational movie, even if there are plenty of cultural markers pointing in that direction—Brooklyn, for one, the Brooklyn already memorialized by Girls.

Maybe the better question would be: what does it feel like to be twenty-seven when you are a girl—a young woman with ambitions not yet fulfilled—in 2013 or 1968? I’m not sure it’s all that different. Moreover, it’s a story we’ve not seen, read, or heard enough about despite the fact that this is 2013 and not 1968.

Now that I have not been twenty-seven for a very long time, I’m absolutely sure that twenty-seven is young.