Or how did nice girls have sex in the 1950s―you know, so twentieth century. In her controversial NYRB piece about two new Sylvia Plath biographies, the critic Terry Castle (who is a friend from before Facebook and I am not going to enter into the Twitter fray) makes a claim about Plath’s sexuality that seems intuitively right to me: “Plath exposed,” Castle writes, “ as no one had before, the quintessential ‘nice girl’ sex-anguish of her time….” While I don’t agree with all Castle invokes to describe that “sex anguish,” the phrase neatly encapsulates how “conventional middle-class American heterosexual women of the 1950s and early 1960s” negotiated their unnamed and often unacknowledged sexual desires.

I say this as a “conventional middle-class American heterosexual” woman―girl we said at the time―who came of age in the murky sex-obsessed years of the mid-century (think Playboy or the Kinsey Reports). Like Esther Greenwood, the heroine of Plath’s pseudonymously published novel The Bell Jar, who in fictional 1953 was determined to lose her virginity in order to know what all the fuss was about, I desperately wanted to know why my parents were so determined to prevent me from losing it. (The language itself is odd when you think about it: losing something you don’t exactly “have.”)

I say this as a “conventional middle-class American heterosexual” woman―girl we said at the time―who came of age in the murky sex-obsessed years of the mid-century (think Playboy or the Kinsey Reports). Like Esther Greenwood, the heroine of Plath’s pseudonymously published novel The Bell Jar, who in fictional 1953 was determined to lose her virginity in order to know what all the fuss was about, I desperately wanted to know why my parents were so determined to prevent me from losing it. (The language itself is odd when you think about it: losing something you don’t exactly “have.”)

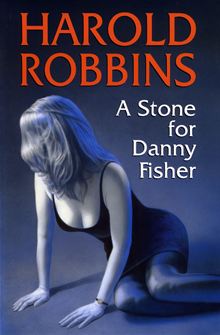

When I was writing my Paris memoir, which revisits my life during those transformational years, I struggled with trying to recreate―remember and understand―just how ignorant and curious one could be as a girl in the 1950s. I had read a few “dirty books” in junior high―a much-thumbed paperback of Harold Robbins’s A Stone for Danny Fisher was a first step in the quest for information. Later, in high school, D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and pirated copies of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. In college, foreign movies, especially French ones, offered hints of what erotic experience might be, but really at twenty, when I first went to live in Paris, I was still utterly in the dark―as it were―about how to have sex with whom. Not to mention how to enjoy it, beyond the daring. Could any twenty-first century girl possibly be as ignorant as we were, as I was?

The new biographical look at Plath’s sexual history (comparing it to my own) has convinced me―if writing my memoir hadn’t already―that sex, on and off the page, is dated. It’s certainly datable. Writing about sex is always hard―the “what is too much” question comes up immediately. But maybe what’s harder is to know what you didn’t know about yourself; that you couldn’t know at the time: to what degree your sexuality did not belong uniquely to you. I was a nice girl, yes, but did I think I was a girl of my time? Did I know I was suffering from “sex anguish”? I do now, but I did not then. And I’m not sure that when I return to that girl in memory, I’m returning to me―or to her.