On the cover of this week’s issue of The Economist, an intriguing headline reads: “Why women should boast more.” I took the hook.

I don’t read The Economist on a regular basis, but its writers often bring an interesting angle to their reporting. In this case, the article ponders a subject close to my heart, the place of of women in academia. Why is it that in most fields, not just science and engineering, “male professors” in the “higher echelons” seem to outnumber “females by nearly four to one.”

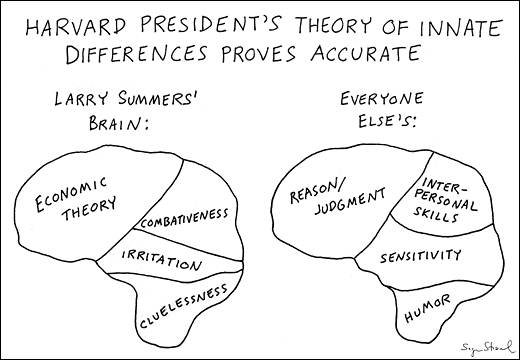

There have been several explanations put forward to account for the disparity―most famously Larry Summers’ incendiary remarks in 2005 at Harvard about the innate differences between male and female brains.

OK. Back to the why are there more men in upper echelon positions, as if we had ever left it.

Or, what is “more” and what is “enough”?

Professor Barbara Walter, at the University of California, San Diego, has proposed a new theory: that “female academics are not pushy enough.” Not pushy enough turns out to mean that they do not, as their male counterparts do, “routinely cite their own previous work when they publish a paper.” Citation―an easily quantifiable marker of importance―counts heavily in the decisions made by appointment committees, and therefore favors male promotion. Exactly why this gender difference in the matter of citation exists remains to be analyzed but Walter’s research evidence suggests that “women see self-citation as a form of self-promotion, and thus look down on it. Men see it the same way, but draw different conclusions.”

Do women frown on self-promotion? Is what’s true in academia also true in the literary world? In my entirely unscientific survey I’ve tried to think of whether I’ve ever received an email from a male writer apologizing in the subject line for his “shameless self-promotion.” Whereas the phrase “shameless self-promotion” has appeared in almost every email message I’ve received over the past few years from women writers apologizing in advance for sharing the news of their book publication, or any public recognition of their accomplishments. I understand the rhetorical gesture without difficulty, and I am sure that I have used the phrase myself in the past. How can you do what you have to do as a writer―promote yourself since your publisher won’t (unless you are John Grisham or E.L. James)–if you don’t beg forgiveness for intruding on your friends and colleagues in order to borrow a few seconds of their precious attention? It would be embarrassing, wouldn’t it, to act as if you didn’t realize that you were indulging in shameless self-promotion, and not just sharing your good news.

Or is shameless self-promotion just a variant of what Sheryl Sandburg means by “leaning in?” Maybe if women shamelessly self-promoted more often, they wouldn’t have to call it shameless self-promotion. Self-promotion would not feel shameful.

As for my latest shameful promotion of recent work, please visit my self-named website www.nancykmiller.com.