By the time I was making the final revisions to the Breathless manuscript, I had been diagnosed with lung cancer―“incurable but treatable,” as today’s oncological discourse codes the situation of late staging. In the final pages of the memoir, where I reflect upon the destinies of the characters important to me in the narrative, I account for the deaths from cancer of my ex-husband as well as that of my Paris roommate. I did not, however, reveal my diagnosis. Despite the truth-telling pact of autobiography that I’ve always held to, despite the fact that I wasn’t sure I’d survive to see the book’s publication, I could not bring myself―as a writer–to end the memoir with that revelation.

Naturally, it was not the only omission in the book―I spared the reader many humiliating episodes of my twenties―but this was different. To end the story on my prospective death would have recast the narrative as cautionary tale, since the girl I was smoked on almost every page. I didn’t want to provoke the moralizing logic that stigmatizes lung cancer patients: you smoked, therefore you got cancer. Invariably, anyone I told of my diagnosis would ask: “Did you smoke?” When I said yes, a horrible silence would ensue during which I imagined my interlocutor’s speech bubble saying with unabashed relief: “I’m so glad I didn’t smoke.” What I heard, spoken or not, was “You brought it on yourself.” But lung cancer, I’ve learned, affects a substantial number of people who never smoked (especially women, and including my mother―no one knows why) and some smokers never develop cancer. Nonetheless, both the current stigma and blame for the former smoker is as pervasive as secondhand smoke, and fundraising for research into the disease suffers from this vision of the disease.

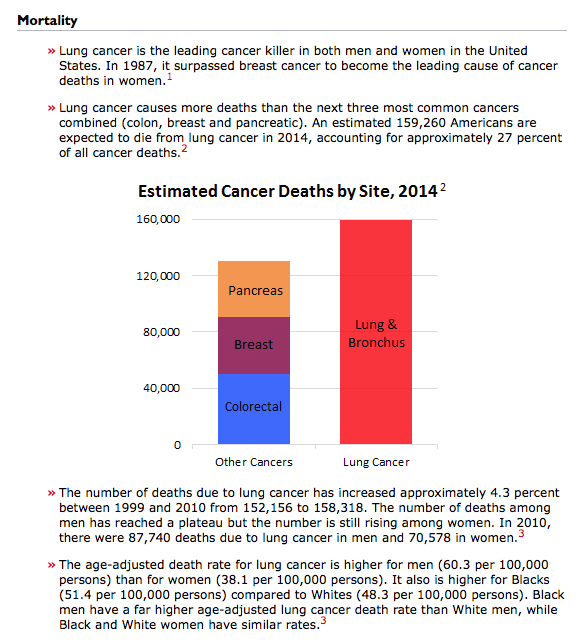

No pink ribbons for us. Lung cancer ribbons are white. It’s difficult, if not impossible to imagine a campaign to “beat lung cancer” with the appeal of “the race for the cure,” not to mention all the pink artifacts you can buy to support research. Of course, it’s easier to picture breasts than lungs, and white isn’t much of a color. Except for the color problem, though, I’m not suggesting that one cancer is “better” or “worse” than another (though some surely are in terms of survival statistics). But the disparity in fund raising remains significant, and lung cancer in women now claims more lives than breast cancer.

Breast cancer can generate the same sense of blame and shame. Miriam Engelberg, in her bitterly hilarious graphic memoir, Cancer Made Me a Shallower Person, shows the response acquaintances typically give when they realize―from her chemo baldness―that the artist has cancer. When she explains that she has breast cancer, the interlocutor typically asks: “How awful, did you have a family history?” And Engelberg imagines a cancer-free person reassuring another cancer-free friend: “So don’t worry―you and I are perfectly safe.” Naturally, we all want to know what caused our cancer, even though in many cases the origin remains a mystery: what could I have done? In one panel Engelberg depicts a support group member saying, “and I think I caused this by eating too much cheese.” Engelberg died in 2006 the year her memoir was published.

Now that Breathless is launched, and its survival rate in book land more or less clear, I’ve wanted to come clean. To that end I’ve created a new project on the website, “My Multifocal Life,” and I will post about the experience of living with cancer from time to time. It makes me anxious to expose myself this way, but it’s important to acknowledge the place of cancer in the world, since statistics suggest that a staggering number of people have or will be having cancer, and to realize that cancer patients are not, in that sense, alone.

October was breast cancer awareness month. November is our turn to clamor for attention and support. Look for those white ribbons.