There’s lots of writing about cancer―memoirs, graphic and prose, blogs, narratological and anthropological studies, science reporting. Most of the writing is bad, by which I mean overly cheerful about outcomes, dull and cliché-ridden (my pet peeves), but in some cases my envyometer starts going wild: Oh this is so good (true to my experience, dark and savage), I wish I had written it myself.

In the category of recent fabulous cancer writers and cartoonists: Miriam Engelberg, Cancer Made Me a Shallower Person; Susan Gubar, Memoir of a De-bulked Woman (and her columns in the New York Times); Lochlann Jain, Malignant; Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Dialogue on Love (and her essays and columns in Mamm). There are other superb memoirs but I’m not looking to create a bibliography. These are twenty-first century texts (except for Eve’s in 1999), and cancerography is changing along with the new drugs―in particular, targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Writer Jenny Diski is publishing her memoir now by installment in the London Review of Books.

Naturally, some things about the illness don’t change. One of them is the waiting room. My friend Jay Prosser, living in England, sends me clippings of Diski’s memoir as it appears. I don’t have a subscription to the LRB, and so I’m dependent on Jay’s excellent clipping service. The memoir seems mainly focused on Diski’s cancer―very much like mine, late-stage lung―and her grouchy persona inspires me to increased bitterness. Unfortunately, even with comparable staging, so many variations within a given cancer exist that it’s rare to find someone having exactly the same treatment. Diski, for example, has undergone radiation and I haven’t (yet). Still, I recognize myself in her weariness and fatigue, impatience with being a patient.

Naturally, some things about the illness don’t change. One of them is the waiting room. My friend Jay Prosser, living in England, sends me clippings of Diski’s memoir as it appears. I don’t have a subscription to the LRB, and so I’m dependent on Jay’s excellent clipping service. The memoir seems mainly focused on Diski’s cancer―very much like mine, late-stage lung―and her grouchy persona inspires me to increased bitterness. Unfortunately, even with comparable staging, so many variations within a given cancer exist that it’s rare to find someone having exactly the same treatment. Diski, for example, has undergone radiation and I haven’t (yet). Still, I recognize myself in her weariness and fatigue, impatience with being a patient.

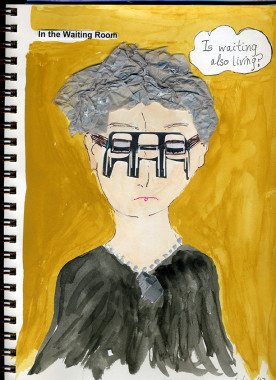

Sometimes the most dispiriting aspect of cancer treatment is time spent in the oncology waiting room. Diski’s seems more depressing than mine―at hers you have to wait for your number to be called―like the line at the fish counter at Zabar’s (my analogy, not hers). But in key ways, the experience is overwhelmingly similar. Here’s a passage from her February 5, 2005 installment in which Diski describes the setting where she watches for her number.

You began to recognize faces and played the new guessing game: which one has the cancer? It wasn’t always easy to tell. What was clear was the distinction between those of us who were having ‘curative’ radiotherapy and those who weren’t long for the world and were having it to help with pain management. Some of the latter arrived in beds pushed by porters, patients all of them grey of face and still, never looking about them at their surroundings. Others more mobile, came having been delivered by volunteer drivers and sat grimly with various wounds and scars from surgery, breathing heavily, none of them looking around at the other patients waiting. We―the less ill ones―stole glances at these patients, those on their last legs or whose legs no longer held them up. Even the most buoyant and cheery patient in the radiotherapy waiting room must have seen the mirror the bedridden held up for us.

And so the distinction, clear at the start, between those undergoing treatments that in theory will prolong life and those for whom the game is up, finally doesn’t hold. Unless you are very lucky―who knows, you might be―while you are there you can’t escape the prognosis that one day you will be waiting in the place of those beyond hope.