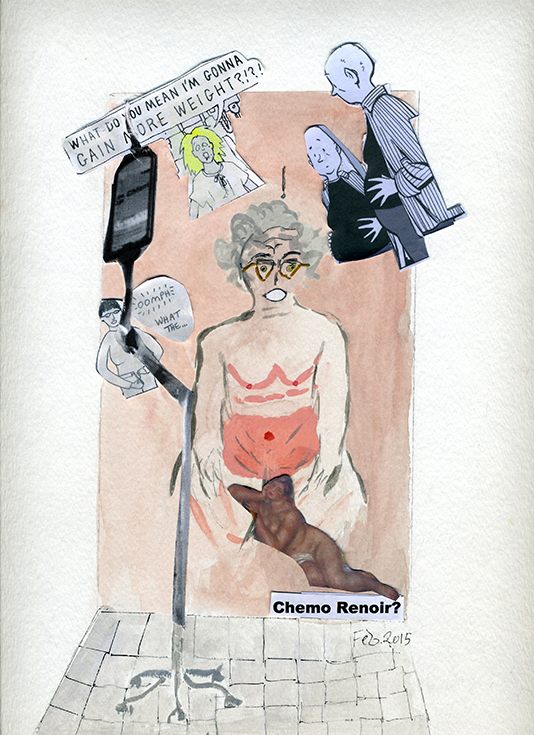

If only we lived in another century. Our rolls of fat would make us desirable and happy. You might think, as I did, that chemo would lead to weight loss, the one plus for some of us: haven’t we all seen images of cancer patients looking skeletal? Indeed, some do, notably the ones very thin to begin with. For those heavier to begin with, it means irresistible weight gain. No one seems to understand why, but when asked the answer is that they like us fat.

When I decided to stop smoking in 1980, I went to a group held at the 92nd Street Y. It wasn’t the more famous “Smokenders,” but the method was the same: ranking, counting and wrapping cigarettes, cutting back as you went along. At the beginning of the first meeting, the leader announced the following in response to questions about what to expect: Some people will lose weight (eye roll), some will gain, and some will stay the same. I knew immediately to which category I’d belong. Within a week of stopping, I had guessed right: twelve lifelong pounds. Thanks to chemo, I’m now subject to the same karma, and learning to dress like a tent.

When I see slender young women smoking in the street, or smell smoke on my students’ papers, I want to urge them to stop. I want to hand out little note cards with typed messages, the way feminist artist Adrian Piper used to, in relation to racism, with lines that say something like: “Dear Friend/You may not realize this but smoking often causes life-threatening disease.” But I know they will shrug and think as I did when their age: “It won’t happen to me. And besides, I don’t want to dress like a tent.”