Old-age friendships are slightly different from those made in the past, which consisted largely of sharing whatever happened to be going on. What happens to be going on for us now is waiting to die, which is of course a bond of a sort, but lacks the element of enjoyability necessary to friendship. In my current friendships I find that element not in our present circumstances but in excursions into each other’s pasts.

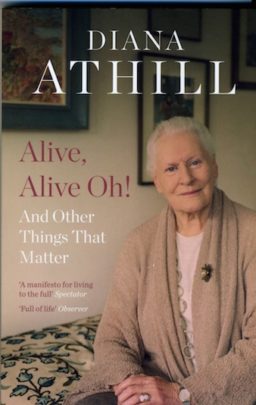

Diana Athill first published these words about friendship in The Guardian in 2010 with the title “The Decision.” She was 93 at the time, and the decision refers to the reluctant acknowledgment that she would have to give up a house she loved, and move to a room (of her own, but just one room) in a home for the elderly. It’s not often that we have an autobiographical narrative by a woman of Athill’s age radiating unmistakable joie de vivre. I read the piece in the kind of shock only something new can produce, as an essay collected in Alive, Alive Oh! And Other Things That Matter (2016). I picked up the book by chance from a table in a bookstore this summer while visiting London, drawn in part by the striking portrait of its author on the cover.

At 75, and already feeling old―a state Athill postponed fully embracing until her nineties–I suddenly saw how much my idea of life in one’s later years has been shaped by my friend Carolyn Heilbrun’s ambivalent stance toward aging. On the one hand, in The Last Gift of Time Carolyn described the singular beauty of feeling life ending―the bittersweet sense of doing some things for the last time in one’s sixties, the joys of being free of the burdens of conventional femininity. But on the other, that frame of mind was made possible only by the conviction that she did not want to advance much further into the life of old age. In fact Carolyn’s perspective on aging depended on the decision―a decision very different from Athill’s―to end her life at some point in her seventies, at 77, as it turned out.

For more than a decade, I’ve lived with Carolyn’s decision to kill herself and its aftermath. I confess that I never fully believed her many unambiguous declarations, published and private, of her intention to commit suicide. A rational suicide still seems implausible to me, and yet it happened. The suicide hangs over my seventies as both warning and invitation. Carolyn was right about so many things. Was she also right about this?

After the cancer diagnosis that inaugurated my seventies, I assumed the disease would make the question moot. I liked the idea that the end of my life would be decided for me. Almost five years later it’s “alive, alive oh.” Much to my surprise (and everyone else’s) the cancer hasn’t yet killed me, so I suppose the question is back on the table–the decision―though it is not foremost in my mind.

What captured my attention in Athill’s reflection on old age had to do with her vision of friendships formed in such late life, for Athill, specifically, in her nineties, with the women in the home. Since I’m not in my nineties, and that decade is not truly on my horizon, what seduced me was the notion she puts forward of “pastness” as forming the basis of friendships made in the perspective of death. I can’t help feeling that in revisiting my friendships in the book I hope to write, I am making “excursions” like those into our past, pasts that seem strangely present to memory. These friendships, of course, are not new ones, but as I return to them, they are renewed, brought back to life.

If Carolyn’s vision of aging was radically different from Athill’s, Athill’s continued pleasure in the changes old age brings reminds me of Colette, another writer who a enjoyed life in all its variety, including growing old and, like Athill, never stopped writing. Colette died at 81 (young compared to Athill). The somewhat autobiographical novel Break of Day, published in her early 50s, carries the tone Athill often adopts when looking back on relationships, and a certain renunciation of sexual life. In the novel, Colette the narrator bids farewell to a man she was in love with, bidding him farewell with a mixture of pleasure, resignation, and nostalgia. He has left, but is he really gone? And is she really alone? It hardly matters. Unlike Athill who never married, Colette met her third husband while creating a novel about how to live after love. What matters is the way Colette conjures the departure of her current lover. She helps him leave by imagining his transformation into many things, but most important, a book still open (livre sans bornes ouvert) and whose boundless pages she might yet fill, an oasis, the novel’s final metaphor, a pause, perhaps a reprieve from an absolute ending.

That is what I wish for my book: that I can still see my friends as they existed in the past, and now continuing with me in memory. They are shifting shape but they are not dead, as long as I write.