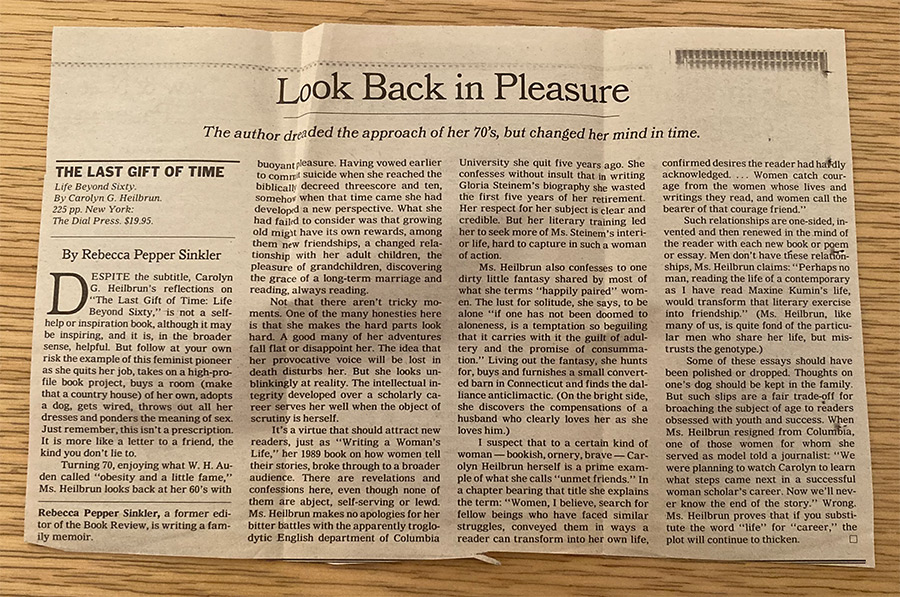

Had I told Carolyn the mismemory story (see part 1) many years later, at one of our weekly dinners, confessed my confusion and embarrassment but also made light of it (I enjoyed entertaining her with accounts of my miseries). She would have been amused, briefly, and then almost immediately irritated, confirmed in her skepticism, more like disdain, of memory itself. In The Last Gift of Time: Life Beyond Sixty, her memoir from the late 1990s, in the chapter titled “Memory,” Carolyn presents an uncompromisingly negative view of acts of remembering, even those of happy memories. Never one to mince words, “experience,” she declares, “once we have processed it, becomes part of our present consciousness and can no longer properly be called memory at all.” It’s “more a matter of history.” Holding on to memories from childhood, moreover, often means remaining tied to “ancient wrongs,” tantamount, especially in later life, to reliving old resentments.

May Sarton, for example, had complained to Carolyn, her literary executor, that biographers and editors had forced her to revisit painful memories, episodes in her life she would have preferred to forget. Of course, Carolyn points out, with an edge of snark, that’s the risk you run if you share your life’s story with readers. Unlike Sarton, she concludes, “I did not wish to be a rememberer.” Not only are memories of past experiences unreliable, but what we might recall from dreams even worse: dreams are nothing but “the detritus of the mind.”

Rereading the memoir decades later, and with my recent performance of mismemory still vivid, I’ve had to recognize that I’m reading a different book. Not least, I had quite forgotten my anonymous cameo as a “friend” bitterly attached to childhood resentments. Nor do I recall the multiple appearances of May Sarton throughout the memoir. Did Carolyn not talk to me about Sarton? Have I completely blanked out, repressed (so much for my octogenarian’s memory) our conversations about the writer?

Spoiler Alert: May Sarton and Carolyn’s relationship with her, will play a starring role as this friendship story unfolds.

Now, though, I’m on the scent and I want now to get it right. At the same time, faced with the evidence of the conference tape, I’ve had to acknowledge that I should also be prepared to get it wrong. As Jenny Diski puts the matter in In Gratitude, “I’m writing a memoir, a form that plays hide-and-seek with the truth. Absolute veracity is not what I’m after.” In this heartbreaking memoir about her terminal cancer diagnosis, Diski also narrates, with the flair of a fiction writer, moments from her tempestuous relationship with Doris Lessing, in whose home she lived for several years, as an adolescent.

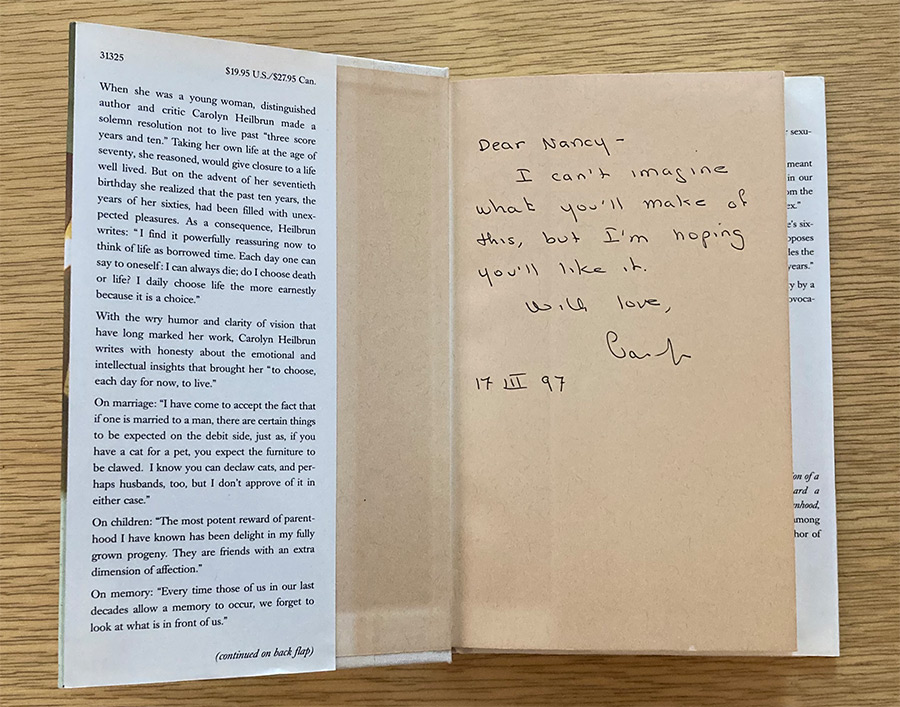

Here, for example, is a scene from my years with Carolyn I feel confident that I remember correctly. It was 1997 and I had returned from a sabbatical in Paris. I was standing at the bus stop on Broadway and 91st Street, saying goodbye to Carolyn, who was headed home downtown after dinner. We had lingered with white wine over our usual, for then, take-out Vietnamese food, and Carolyn had given me The Last Gift of Time. She must have written the entire book in the months I was away in Paris and waved off the accomplishment. Here’s the memory hitch. Carolyn’s inscription to me is dated March 17, 1997. I would not have returned from Paris; the bus top scene would have had to take place later that fall, and yet I see us standing there, talking. This is also known as consolidation, unconscious reimagining.

Did I like the book as Carolyn hoped I would? What did I make of it then? I was, as were many readers, filled with admiration for Carolyn’s stylish writing. I still am. But even rereading the book decades later, the memoir’s premise still overwhelms and undercuts the charm of the individual chapters. Here’s why. Carolyn announces in the preface that she would determine how and how long she wished to live after seventy: “Quit while you’re ahead was, and is, my motto.” Did I believe that this fierce and feisty woman, greatly annoyed at having to wait for the poky Broadway bus, would quit the way she did, die from suicide at age 77? No, but the prospect hung over the last years of our friendship. And then I had to believe it.