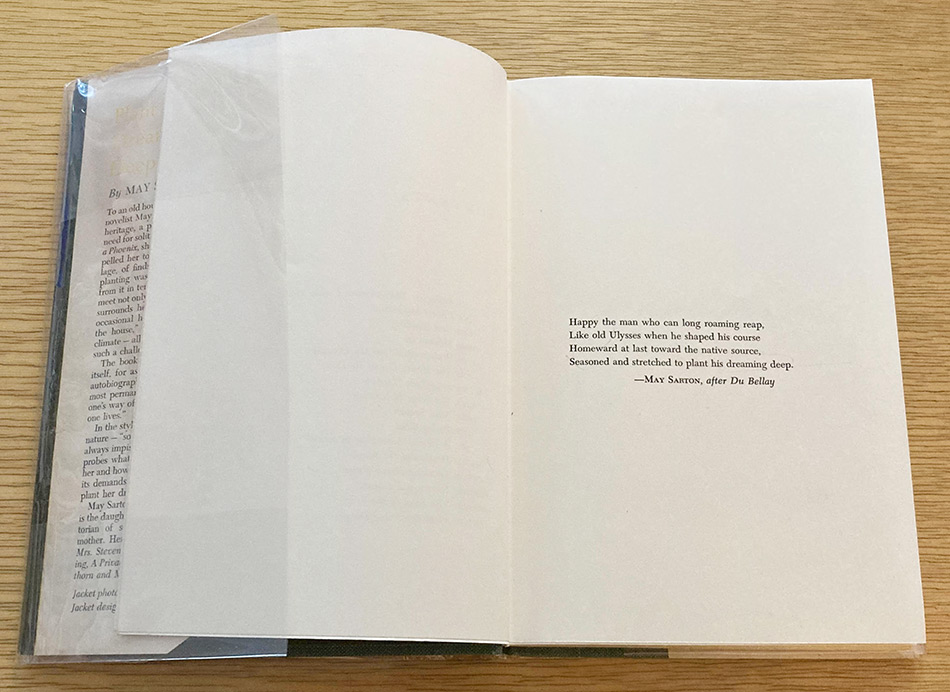

A thought experiment. Suppose I had read Brooks Atkinson’s review (see part 5) and bought May Sarton’s memoir Plant Dreaming Deep. I would certainly have been arrested at the door by the author’s use of a famous sixteenth-century French poem as an epigraph to situate her project: “Heureux celui qui, comme Ulysse, a fait un beau voyage.” The poem’s title is also its first line in which Du Bellay imagines the return of Ulysses to Ithaca: “Happy the man who…”

Sarton translates freely the first 3 lines and then invents the 4th. That line contains the phrase that gives her memoir its title. In Du Bellay’s 4th line, the hero returns to the land of his ancestors: “To live with his parents the rest of his life.” In Sarton’s version, “old Ulysses” returns: “Seasoned and stretched to plant his dreaming deep.” Sarton has made other changes in her translation to serve her own journey, but this line is the most deeply transformed.

Here’s where I stumbled: Sarton is not returning home to live the rest of her life in her parents’ ancestral land. It’s just the opposite. In the first chapter of the memoir, Sarton describes in detail, the importance of transporting her deceased parents’ furniture (originally from Belgium, where she was born) to her new chosen home in New Hampshire. Sarton’s “ancestor” is the portrait of an eighteenth-century gentleman, with a posh name: Duvet de la Tour. According to Sarton’s parents, he was “the ancestor, as if there had been no others” (17).

In 1968, I suspect that I would have wanted to save Du Bellay from Sarton’s recreation, not least because that line “Seasoned and stretched to plant his dreaming deep” simply does not scan for me. In his review, Atkinson comments that “the esoteric title derives from one of her own verses” (well, she does sign, “after Du Bellay”). Esoteric is one way of reading it. That line still doesn’t make any sense to me, whether the planting is material (i.e. a function of gardening) or symbolic, imagined. Certainly, it has nothing to do with Ulysses.

So, ok, I imagine I would have, frowned at Sarton’s gesture. What, she has rewritten the meaning of this classic poem to cast herself as the hero of her life, only in reverse? I’m sure that had I encountered the lines in 1968, I would have rebelled. Why frame your very American project with a classic of 16th-century French literature?

I was nothing if not a rabid Francophile.

She has violated the original.

But that was before French feminists transformed the classics in the 1970s: Hélène Cixous’ “The Laugh of the Medusa,” for example, in which feminists liberate the language and its ancient myths to suit their own needs. Now (post 1968), I can freely ponder the wholly invented fourth line: What might it mean to plant your dreaming deep? I might even embrace the innovation, as Carolyn did, and try to understand why Sarton created this metaphor to account for her project. I’m not there yet, though, I’ve begun to see through the correspondence, how deeply (that word) self-mythification attracts the Carolyn of 1968.

Better Ulysses than Penelope?