In her reply to Carolyn’s harsh critique of her novels, Sarton takes the high road: “Dear woman,” she protests (and I love this), “you simply cannot use the categorical imperative,” with her. She’s a writer, after all, and goes on to defend her aim as a fiction writer: to portray “a positive vision of life” in contrast to the “homosexual novel” that shows “deviance through its most degraded aspect.” It takes courage and “a stubborn will to survive,” she proudly declares, and in “survival there is triumph.”

Two years after her original fan mail, Carolyn explains her impulsive gesture: “it was written because I wanted to reach you, I guess…” Carolyn continues, almost surprised by her expression of need: “you would never guess from it how reticent and ungiven to personal remarks I usually am,” adding that she “regretted the letter as soon as it was gone.” Then a step further in this uncharacteristic mode of insecurity, she admits to her fear that Sarton would write her off “as a mistake.”

The effect of reading these letters for the first time jarred me out of any conviction I had enjoyed in thinking I knew my friend well, even intimately. I could not recognize the tone of this writing. I still cannot. Carolyn fearing she’d be written off as a mistake—a mistake! —was not the woman whose unapologetic confidence I had spent more than twenty years admiring.

Carolyn highlights Sarton’s “need to ‘fight it out’” as expressed in her works, which she shares: “I want to fight about conventions sometime too.” Which conventions? And what exactly of Sarton’s universe fascinates Carolyn? “You affirm life and reveal what has not been seen before.” Here is what she finds exciting: Sarton’s “ability to affirm, to embody, new loves” and experiences, “relationships for which the language has not yet been found.”

In what feels now unbearably touching to me, Carolyn (now Carol to May) in a postscript offers to send Sarton a detective novel she had published under the pseudonym Amanda Cross, without naming herself as its author. A coy moment.

Two letters from Sarton to Carolyn at the Berg came in a separate folder from Carolyn’s letters but along with them. (I believe that Sarton kept the originals of Carolyn’s letters and that the ones in the NYPL belong to the Sarton archive. Carolyn’s papers are at Smith.) These look to be battered copies of carbons on paper that had turned brown with age. Sarton begins her reply to Carolyn’s most recent letter, explaining that she had had house guests and no time for letter writing. After an anecdote about her furnace on the blink and her parrot shivering with cold (these details of country living will continue to punctuate the correspondence), Sarton plunges into the epistolary exchange with enthusiasm and admiration. She dismisses Carolyn’s anxiety that she’d be rejected or ignored (“written off”). On the contrary, her arrival on the scene, Sarton reassures her, was “one of the very best things” that could have happened and looks forward to their meeting “face to face.”

Carolyn never hides her reservations about Sarton’s novels, which, unlike the poems and autobiographical works do not, she feels, “fully embody” Sarton’s vision. And tacitly accepts Sarton’s resistance to her categorical imperative. “I cannot tell you what to write,” she acknowledges, almost reluctantly, but “what a relief to be categorical for once and get away with it.” (When did Carolyn not get away with being categorical, one of her major modes?)

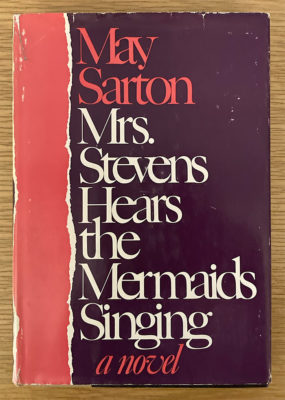

In turn, Sarton, defends her work as a novelist, with references to Jane Austen and Turgenev, reminding Carolyn that a lot takes place “between the lines.” Then with no segue, in the very same paragraph, she shares her view of the Amanda Cross detective novel Carolyn had sent her. Sarton does not mince words: she found the book “terribly boring,” not to mention “pretentious” and “academic.” By contrast, in a long single spaced second page, she goes on to celebrate her accomplishments as a writer, praising her own 1965 novel, Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing, as a triumph. Sarton then compares her accomplishment at having created a portrait of “the woman as homosexual artist in a fictional form” that is more successful than Woolf’s in A Room of One’s Own. (!) Modesty is never her strong suit.

Sarton finally signs off expressing her desire to continue working on what will become the “journal of solitude,” and wishing Carolyn the same for the book she is working on, the book on androgyny. (Both books would be published in 1973.)