What I remember about Carolyn with an onslaught of intellectual agita is not solely the artifact of a major death anniversary, but also the surprising effects of an earlier encounter with an interesting young woman. (View Part 1 and Part 2)

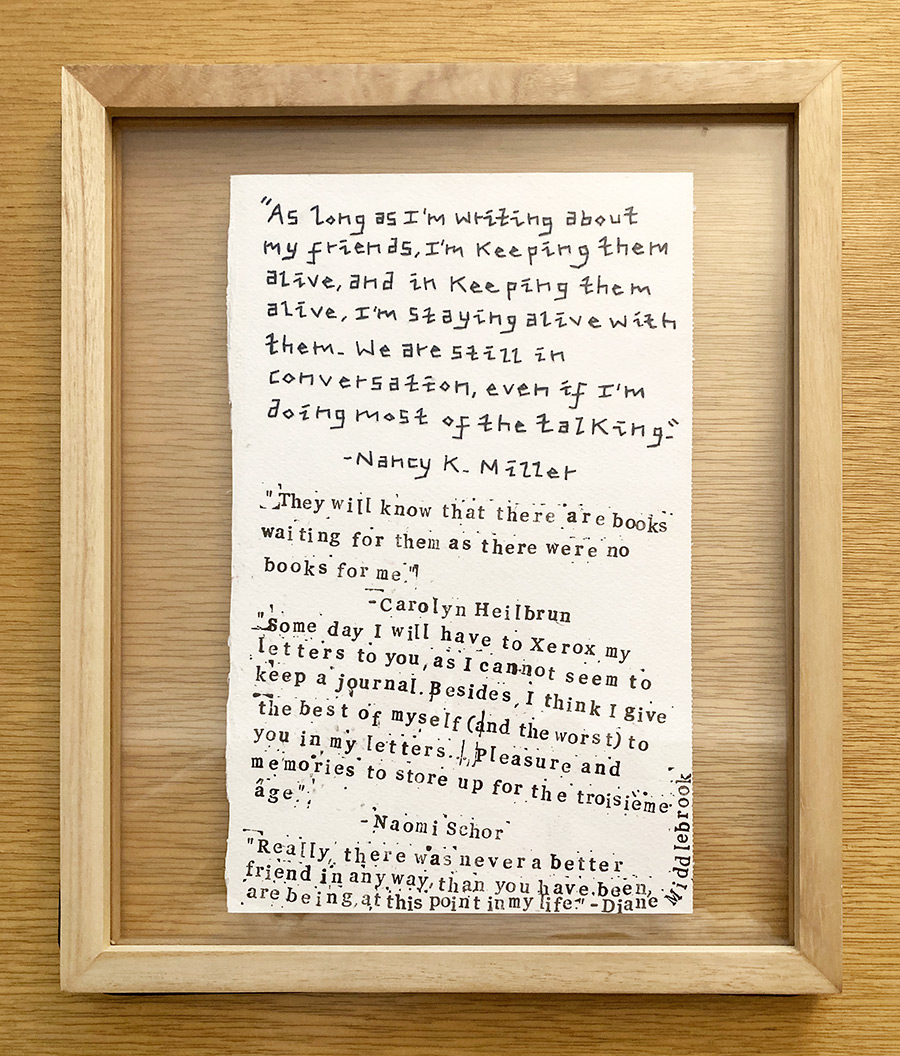

At the end of a conference in England on feminist friendship in February 2020, just weeks before the Covid-19 pandemic became official, I met Storm Greenwood, a young British graduate student. (Storm’s mother had named her daughter after the English journalist and writer Storm Jameson.) Storm knew my work, and as an example of what she calls her feminist practice of “devotional citation,” had created a beautiful embroidered and hand printed text, featuring quotations drawn from my friendship memoir, including lines from Carolyn. Once home, I had the artwork framed and it sits on a table in my study, a poignant memory prompt.

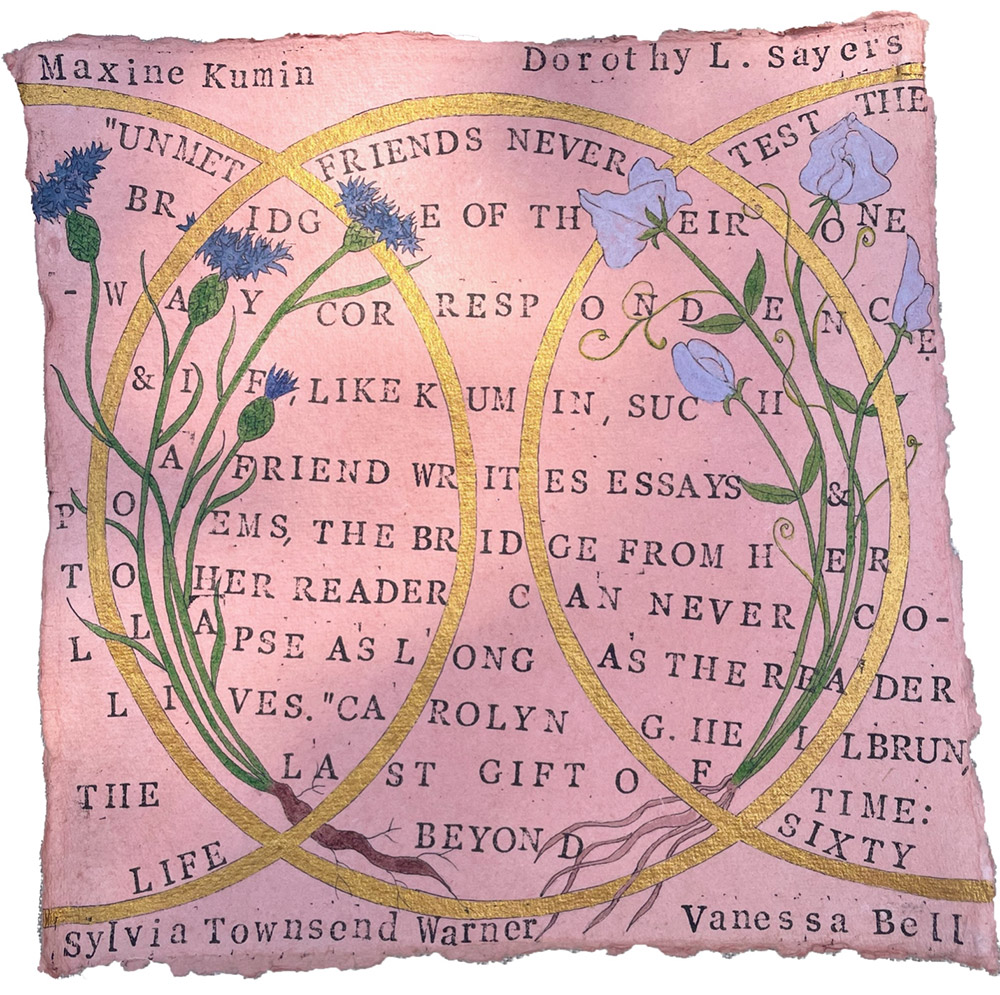

Three years later, this past spring Storm came to New York on a research trip for her PhD thesis. I invited her to meet at the only decent coffee shop near me (given the post-Covid devastation of my neighborhood, the very existence of the place is quite remarkable). The thesis had two parts, she explained over reliably good coffee. One was Carolyn’s notion of the “unmet friend,” a precious if imaginary relationship of her invention and that she describes in The Last Gift of Time; the other, the role of flowers in the life and writing of the writer May Sarton, for whom Carolyn had been the literary executor. As an integral part of the dissertation, Storm also created visual texts she describes as “illuminated manuscripts featuring botanical paintings entangled with citations.”

Storm had traveled here to look at the Sarton correspondence held in the Berg collection at the New York Public Library. During her research, she came upon a folder of letters from Carolyn to Sarton, 70 all told, from 1968 to 1994. (There also was a separate folder of two early letters, copies of carbons, from Sarton to Carolyn.) Storm had not planned to analyze the relationship between the two women as part of the thesis, she said, but hoped to publish their correspondence after completing the dissertation. Because she knew that Carolyn had been a close friend, Storm shared snippets and letters from the archive. I was immediately captivated, but equally shocked.

Now, I had always known that Carolyn had been May Sarton’s literary executor, and in that capacity had, on occasion, visited the writer in New Hampshire and Maine. Sarton famously was a difficult woman and Carolyn, as I recall, shared that view; that’s how Carolyn typically referred to Sarton (other friends remember this as well). I recognized the writer’s name on its own, of course. Sarton had by the late 70s become well known in feminist academic and lesbian circles, but somehow, I had not read her work. I still can’t quite say why, since surely, I would have been interested in a woman writer Carolyn thought important enough to wish to become her literary executor.

These letters revealed to me a Carolyn I had not known, not only because the correspondence began in 1968, almost a decade before the two of us had met at Columbia, but also in spirit: this was another Carolyn entirely, a younger version, passionate and humble, a woman I would have loved to know. Through the letters, I encountered a person I would meet only through the scrim of her correspondence. I could, however, try now to examine the relationship between the two women and to discover that incarnation of Carolyn, soon to be “Carol,” through their exchange, however belatedly.

The letters Storm shared sent me back to reread the “Unmet Friends” chapter in The Last Gift of Time that had in part inspired her thesis. My first moment of discomfit was to notice that I had remembered the chapter’s title incorrectly, as “The Unmet Friend,” in the singular (though I had the title correctly in my book). I had understood and embraced the notion of unmet friendship through Carolyn’s identification with and admiration for Maxine Kumin. Kumin fulfilled perfectly and movingly the conditions of Carolyn’s invention: a person so close to her biography (born a year apart, Jewish, in a long marriage with three children, a lover of animals—though, too bad, Maxine also loved swimming, which Carolyn hated, and went to Radcliffe not Wellesley), that it’s as if the two were destined to become friends. Such a friendship, Carolyn argued, would be timeless, because it emerged from acts of reading, and therefore could remain unaffected by circumstances. I was so enamored with this idea that I wrote a short essay on the fictional relationship between the two women. For me, then, and in memory, Kumin was the concept’s unique inspiration and incarnation.

Rereading decades later, I was astonished to see that May Sarton, whom Carolyn had met personally and known for many years, also figured in the chapter, alongside the portrait of Maxine Kumin. In one section, for example, Carolyn focuses on the careers of the two women, and the hostile reception both had suffered as women poets qua women. To make the point, she cites a published interview in which Kumin answered a question put to her about something Sarton wrote about women artists and the nature of creativity. Kumin disagreed.

As she once said of her relationship with Anne Sexton: they were very different poets.

May Sarton died in 1995. The Last Gift of Time was published in 1997. Why did Carolyn, the most logical and economical of writers, feel compelled to include Sarton (true, Gloria Steinem also makes a cameo), in a portrait dedicated to a woman she had in real life never met? Was this a way of continuing her role as literary executor, a relationship that death had not ruptured, writing in memoriam?

If I was astonished to encounter May Sarton in “Unmet Friends,” what stunned me in returning to the memoir, was a chapter devoted entirely to her: “A Unique Person.” I remembered nothing of this chapter, not a single word. It was as if the chapter had been added to a later edition of the book. (Of course, it had not.)

Should I be banished from the memoir club? As I’ve said, what I retained from my initial reading of the memoir was Carolyn’s dramatic statement that while she had enjoyed life in her sixties, and in ways she had not expected, she did not desire to live past 70. Having reached that age, however, she had chosen to remain alive, and pulled back from announcing a fixed date for her death. Yes, she still planned to end her life on her own terms, but until then would enjoy time’s last gift: the finite pleasures of a consciously chosen life. Reviewers and friends sighed a collective relief: not yet and maybe never. But returning to the memoir now, the suicide accomplished, I’m beginning to see other, intertwined threads to the mystery of her personality, key among which was her fascination with Sarton the woman, as well as the writer.

Put another way, and reluctantly recognizing Sarton’s tutelary presence throughout the memoir, I must acknowledge that I completely missed the importance of this relationship in Carolyn’s life while she was still alive, not least in her books (which failure is more significant?).

Can I repair my lapse now through the evidence of the archive?