Over the past decade, students have been thrilled by their forays into the archive. I’ve been skeptical but also intrigued by their fascination — both what hooks them and why, especially when lured by the siren song of the epistolary. And so here I am limply following in their path, intrigued by the promises of truth and revelation that letters seem to hold. I’m also drifted back in memory, caught in the nets of the 18th-century epistolary novel, where my own graduate student days began. But it’s as though I had not remembered that those correspondences were fictional. I’m reading in full flush of naiveté, almost forgetting that my 20th-century characters both wrote fiction themselves.

Were the letters I composed for over sixty pre-email years a wholly veracious account of what I felt at the time? I may well have thought so in the moment of writing. I hope so now.

Dear Reader, please bear with me: I’m taking these letters between two prolific women writers à la lettre, as if I were I’m following the traces of a transparently true story. A story whose origins were first retrieved here, in the archive.

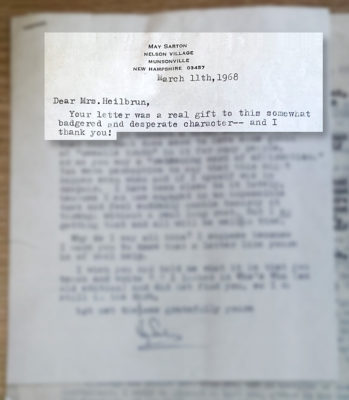

“Dear Mrs. Heilbrun,” Sarton writes, March 11th, 1968, answering Carolyn’s first letter almost immediately. Her reply arrives typed on personalized note paper with the identical format as Carolyn’s with the home address printed in blue ink at the top of the page. Sarton thanks Carolyn for her letter and responds to her flattering comments about Plant Dreaming Deep. Carolyn had been “perceptive,” about her writing, she acknowledges, adding that she found the letter “of real help.” But wait. Who exactly is this new correspondent? Sarton had hadn’t found Carolyn up in an “old edition” of Who’s Who (how important could she be?). Despite feeling herself “still in the dark” about Carolyn’s status, Sarton signs off with expressions of gratitude.

The correspondence picks up again in the winter of 1970. Carolyn reminds Sarton that she had sent a letter praising Plant Dreaming Deep, the previous March. She has since been busy reading everything that Sarton has written (a lot) and confesses to feeling “seized with a desire” to write about her work. To that end, Carolyn sends articles and reviews already published by her that she hopes will persuade Sarton that this is a good idea. Carolyn describes herself, in response to Sarton’s earlier request to know more about her, noting her book contract and advance with Knopf, and a grant from the Guggenheim to finish the book. Nonetheless, despite these previous commitments, she wants to write about Sarton, and proposes that they meet. She’d even travel to New Hampshire if Sarton doesn’t plan to come to New York.

Sarton not surprisingly admits to being “thrilled” at the idea that Carolyn would write about her work. And launches the complaint she will continue to make for the rest of her very successful career: Despite having received some flattering reviews, she has “suffered from having had almost no serious critical attention.” Carolyn, she’s convinced, will change all this, get Sarton the recognition she deserves.

Carolyn’s letter of December 7, addressed this time to May Sarton (the Miss is gone), is almost two office size single-spaced pages filled with suggestions on how Sarton might improve her novel writing technique. Carolyn does not tread lightly. Sarton’s next novel, she insists “must not make use of a narrative voice.” Rather, she suggests, Sarton should follow Henry James’s narrative practice of “single consciousness in The Ambassadors.” The reader’s “awareness” should align with that of the central character, that is to say, Strether’s.

(Very near Carolyn’s suicide, in a last and posthumous essay about reading, rereading, and how to live, Strether and The Ambassadors return. It’s as though for Carolyn, that novel almost literally names the inner quandary at the heart of a writer’s life, and she refers to James elsewhere in writing to Sarton. While I find it hard to recognize anything remotely “Jamesian” in Sarton’s fiction — or in Carolyn’s detective fiction, for that matter — I can only ponder Carolyn’s own long, fervent attachment to the author.)

Carolyn’s letter is filled with as much praise as critique. The autobiographical works, she declares (no hedging), are “superb because of the voice you have found,” and that what Sarton says in that voice is something completely new and important especially for women artists. “You are a poet, and with a poet’s voice”; Sarton should “construct a novel as though it were a poem, as you have done with the autobiographical works.” The letter ends both with an apology for the comments and an expression of faith in Sarton’s future: “You will become quite a figure, before you’re done.”

The seeds of transaction are planted deep, very deep.